- Home

- Daniel Quinn

Dreamer

Dreamer Read online

DREAMER

Also by Daniel Quinn

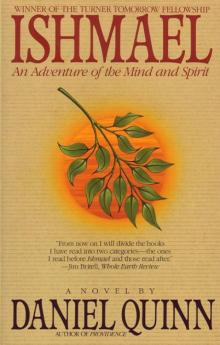

Ishmael

Providence: The Story of a Fifty-Year Vision Quest

The Story of B

My Ishmael

Beyond Civilization: Humanity’s Next Great Adventure

After Dachau

The Man Who Grew Young

The Holy

If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways

Tales of Adam

Work, Work, Work

At Woomeroo: Stories

DREAMER

A Novel

By

Daniel Quinn

Copyright ã 1988, 2013 by Daniel Quinn

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system—without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages for inclusion in a review.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons,, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Front Cover Art © choikh – fotolia

For Michael Schillace, who

wouldn’t let me get away

with neglecting this book

INTRODUCTION

Dreamer was written in 1985-86, in between the sixth and seventh versions of the book that would ultimately become Ishmael (which was version eight). Although it was written in New Mexico (at a time when I and Rennie, my wife, were publishing The East Mountain News), it's set in Chicago and drew upon my experiences there as an editor and freelance writer and my close association with several of that city's fine graphic designers, particularly the much-missed David Lawrence.

The manuscript was agented by that "Prince of Agents" Scott Meredith, whose readers were, I'm afraid, not quite sharp enough to recognize some of its fundamental flaws. It traveled from publisher to publisher for a year before landing on the desk of Melissa Ann Singer at TOR Books. I was fortunate in that she enumerated its flaws in detail but was sufficiently impressed with the book to give me a chance to remedy them. I agreed with her assessments entirely, provided an outline, which she approved, and went ahead with the revision.

It came out in softcover in 1988. Although included among the year’s best in Ellen Datlow’s influential annual review of fantasy, it was not a commercial success and was soon out of print. It nonetheless continued to enjoy an underground notoriety and in 1995 was included in a “Horror at the End of the Century” list published in the New York Review of Science Fiction.

TOR reverted the rights to Dreamer to me in 1997, and I’m pleased to be able to make it available once again in this new edition.

Daniel Quinn, 2013

PART

ONE

I

GREG DONNER WOKE to the buzz and clatter of an old neon sign hanging just outside the window. He watched it splash red and green by turns on the dingy, cracked ceiling and wondered where the hell he was. Still half asleep, he wasn’t particularly worried about it; it would come to him in a moment.

There was something familiar about the bed he was lying in, with its worn chenille bedspread and its hideous white-painted iron scrollwork at head and foot. It was an old, tired bed, and it sagged under his weight. Awake, Greg would have known it immediately as one that had once stood in an attic room in an Iowa farm-house. Now, in his dream, running his fingers through the old chenille, he simply had a vague feeling of nostalgia and comfort.

Glancing at the window, he remembered that the neon sign was hanging over a cut-rate liquor store, and he wondered why they bothered to leave it on all night: without looking at his watch, he knew it was three o’clock in the morning. And, without knowing exactly where he was, he knew he had a long walk to get back to his apartment. Fully clothed, even down to his shoes, he had to struggle to free himself from the clinging grip of sheets and bedspread.

He stood up, twisted his clothes back into place, and looked around. Except for the bed, the room was completely empty. It

looked like an office that had been vacant a long time. Thinking this, Greg remembered where he was and what he was doing there. This was his lawyer’s office—or at least the space in which his lawyer conferred with clients. The exact nature of his legal problem eluded him for the moment; he’d left something undone, and a heavy penalty was about to be imposed on him. Even a term in prison wasn’t out of the question.

And so Greg, who managed his waking life without a lawyer, had come to consult his lawyer. With the sure, false memory of dreams, he knew that the lawyer had been furious with him, had berated him like an angry parent. Greg wouldn’t be in this mess had he followed past advice, and the lawyer had no patience for wrongheaded clients. He washed his hands of him. Gathering up his papers, he had stormed out of his own office, slamming the door behind him.

Weary and discouraged, Greg had crept into the ancient, sagging bed, and gone to sleep. It didn’t matter now. He’d find another lawyer in the morning, a lawyer of a better class, who didn’t have his office over a liquor store.

It took him a while to find the door, because it was hidden behind the tall scrollwork at the head of the bed. This was his own doing: He’d taken the precaution of using the bed as a barricade against the lawyer’s return. He shoved it aside and tried the door. Locked, of course; the night watchman would’ve seen to that. Greg shook his head in mild disgust; should have anticipated this, should have planned more carefully. No matter: the lawyer had to keep a key somewhere. Thinking about it, he winced, because he suddenly knew exactly where the key was. He saw it plainly on a ring in the lawyer’s pants pocket. Although the man’s face was a blur, his glen plaid suit was unforgettable, and it was hanging in a closet miles away.

He fought down the beginnings of panic and tried to consider the problem calmly. There had to be a key somewhere on the premises; in fact, it seemed to him now that there was actually a law to that effect. But when he looked around, it was without much hope. The barren room offered almost no hiding places. Then, with a sigh of relief, he realized where it had to be: under the mattress. But, folding it back, he found nothing but a rusty, twanging wire grill. Greg closed his eyes for a moment to visualize the action of hiding a key under this mattress: it would obviously fall through the grill to the floor.

And there it was, exactly centered under the bed, nestled in a disgusting flock of dust bunnies. Greg fished it out, wiped it off on his pants, and opened the door. This really is a seedy building, he thought as he made his way down the narrow, grimy hallway and even narrower stairway to the ground floor. He began to wonder what he’d do if the front door was locked as well. But it wasn’t, and he slipped out into the dead still night. He paused uncertainly. The street was totally unfamiliar, totally deserted, totally silent, except for the rhythmic clacking of the liquor store sign overhead. Instinct told him that he was in Uptown and that he was facing Lake Michigan. This meant that home was to his right. Having no other guide, he followed his instinct.

The city was uncannily quiet, with every window black, every car motionless at the curb as though abandoned during a general evacuation. Even the distant hiss of traffic was missing. The streets had the sinister feeling of a backlot film set deserted since the thirties, when long black Packards prowled by with tommy guns bristling at the windows. His footsteps echoed hollowly off the gray buildings around him, and he could well believe they were just facades propped up from behind by haphazard structures of two-by-fours.

Having nothing else to do as he walked, he began counting streetlights: a useless activity, since he didn’t know how many he’d have to

pass before he reached his own neighborhood. And, having nothing else to listen to, he listened to the echoes of his footsteps. Footsteps, he thought, are signatures—like voices, like faces, like fingerprints—but no one ever listens to them. Smiling, he thought he began to recognize himself in them: they were tall, good-natured, humorous; a bit awkward, not entirely regular, sometimes seeming to miss a beat, sometimes seeming to add a beat. He frowned, listening more carefully. There were far too many extra beats; it was as though the echoes had developed an echo of their own—as though his footsteps had twinned. With a pang of apprehension, he realized he was being followed through the dark, deserted streets of Chicago.

It wasn’t until midafternoon, while reading a story in the New York Times about a lawyer being sued for malpractice, that the image of a glen plaid suit hanging in a closet popped into Greg Donner’s mind. Wondering what a glen plaid suit hanging in a closet meant, he laid the paper down on the library table. “Keys in the pocket,” he thought. Then it all came back to him, and he smiled, remembering the grotesquely furnished office and the clacking neon sign, and the key hidden absurdly under the mattress. He sighed and glanced again at the news story, turning it around in his mind, looking for an angle. He decided there wasn’t one and turned the page.

At age thirty-two, Greg Donner was a moderately successful freelance writer, his specialty being work-for-hire. His clients were not generally publishers but rather book packagers, canny hucksters with keen eyes for the marketplace, whose “packages” included an idea, an author, consultants when needed, market strategies, product management—and ultimately, of course, a manuscript. When they were in vogue, Greg had written about astrology, martial arts, running, assertiveness, and body building, and had tried to satisfy the reading public’s insatiable appetite for competence and success with a dozen or so self-help and how-to books. None of them appeared under his name, none had the slightest pretension to literary merit, none was memorable, none had reached the best-seller lists—but then none of them had failed to produce a healthy return on invest-ment, and that, in the wicked world of the capitalist West, is the general idea behind book publishing. He was in the bread-and-butter end of the business and was content to leave the haute cuisine to others.

Three weeks earlier, he’d gotten a call from Ted Owens, a literary agent and book packager in New York City, who asked him if he wanted to do a book on personal computers.

Greg had groaned. “I’ve done two in a row.”

“I can believe it,” Ted said, and spent a few moments thinking. “I’ve got something else on a back burner if you want a change of pace.”

“Go on, tell me about it. My tongue’s hanging out.”

“One of the kids on my staff came up with this, and I’m pretty sure when nobody’s in the office it goes ‘Gobble, gobble, gobble.’ You get me?”

Greg said he got him.

“Okay. It’s an annual called Bizarre.”

“Bazaar, as in the magazine?”

“Bee-zarre, as in weird and strange. It’s supposed to be a compilation of the weird happenings of the year, with about one-third of the text in cute illustrations.”

“What kinda weird? UFOs? Abominable Snowmen?”

“No, not that kind of stuff. Hold on, let me get the file. . . . Okay. A few weeks ago a fifteen-year-old kid in Grosse Pointe Woods, Michigan, walked into a dentist’s office, pulled a gun, and said, ‘Take the braces off my teeth or else.’”

“Uh-huh.”

“Okay. This one’s more recent. A ninety-three-year-old woman in West Palm Beach, Florida, was literally spooked to death by the U.S. government, which kept sending her letters saying she was no longer eligible for social security because she was dead. When she went on bugging them about it, they decided to appeal to her husband. They sent him a letter saying, ‘Look, your wife can’t receive social security, because she’s dead, get it?’ That really got to her, because her husband had been dead for nine years. She died of heart failure the next day.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Okay. This one’s pretty good. Prince Philip recently visited a factory town in North Wales where better than twenty percent of the people are unemployed. He told a crowd, ‘Everybody talks about unemployment. We would do much better to talk about the number of people who are employed.’ You want to know why?”

“Yes, indeed,” Greg said.

“‘Because,’ the prince said, ‘there are more of them.’”

“A penetrating observation. Sensitive, too.”

“Yeah. You get the idea?”

“I get the idea. The illustrations really sell the book. The text is virtually just captions.”

“Yeah, I’d say so.”

“I think it could go, Ted. And if it goes . . .”

“Right. That’s the point. If it goes, it’s an annual event. Easy money in everybody’s pocket.”

Greg thought for a moment. “And what are you looking for—a sample to show around?”

“Right. Fifty pages or so, with a lot of variety. Probably a waste of money, but I gotta give the kid a chance. You know me, I got a soft heart.”

“Sure, Ted,” Greg said, “just like heat-fused sand.”

Greg started with two clipping services but, checking what they supplied against his own gleanings, found they were rarely able to spot the bizarre when it occurred in straight news stories. They both sent him the story of Fred Koch, who got tired of hearing his name mispronounced Kotch and legally changed it to Coke Is It, thereby enraging the Coca-Cola Company. They both gave him the story of a mail carrier who sprayed a toddler with dog repellent because he wouldn’t move away from a mailbox. But evidently neither of them saw anything bizarre in the story of a security guard at Beirut Airport who tried to win a promotion and a raise in pay by hijacking a Boeing 707 and threatening to crash it into the presidential palace.

So he reconciled himself to spending the spring and early summer inside the palatially seedy Chicago Public Library, alongside derelicts nodding over their unread magazines and midschoolers whispering over their term papers. He had once described his line of work as offering long hours, low pay, no fringe benefits, no security, and no future, but it suited Greg perfectly, and he couldn’t imagine himself in any other.

“Salesman’s Dream Foretells World’s End,” the headline said. A used car salesman in Seattle had quit his job, sold his house, and started gathering followers to accompany him to the top of Mount Ranier to observe the end of the world “in the not too distant future.” In itself, it was nothing, but Greg made a note of it in case something came of it later. Then he allowed himself another look at his watch. Five to six: quitting time. The worst of the rush hour would be over and he might even get a seat on the bus. He closed his notebook, slipped his pens into his shirt pocket, and got up to shelve the newspapers he’d been working on. On his way out he stopped in the men’s room to wash his hands; after a day of paging through the New York Times, they were as black as a coal miner’s.

Stepping out onto Michigan Avenue, he decided to walk, at least to Oak Street. It was one of the handful of days Chicagoans receive from the gods as a break between the fury of winter and the swelter of summer, and Greg didn’t feel like wasting it in a bus. Besides, he hadn’t made his Michigan Avenue tour in a week, and there was no better time for it than now, when the office workers and shoppers had taken themselves off to their suburbs and left the area to its elegant residents.

Greg had grown up a country boy, in a small town outside Des Moines, and so Chicago, being a collection of villages, suited him. He lived in the village known as New Town, where the snooty, lake-facing piles on Lake Shore Drive turn their backs on bar-cluttered Broadway just a block west. Within a ten-minute walking radius of his apartment, he could buy groceries, hardware, books, and records, hear live folk and rock music, go to the movies, and take his choice of Chinese, Japanese, French, Italian, or American cuisines. It was enough. It was like his work: interesting and varied, but mile

s from glamorous.

The Near North was another village: life in the fast lane, packed with strip joints and clip joints and nightclubs and high-ticket restaurants where conventioneers could leave behind their bucks. Its natives tended to be young, trendy, single, well-heeled, and determined to be in the right place at the right time. But for Greg, the north Michigan Avenue village was the epitome of City: sleek, cool, dignified, civilized, above fashion. Its modest proportions suited him. Park Avenue or the Champs-Elysées, he was sure, would overwhelm him.

After crossing the bridge over the Chicago River, he spent half an hour browsing in a bookstore and left without buying anything. He considered stopping for a drink at The Inkwell and decided against it. He considered calling Karen to see if she wanted to meet for dinner somewhere—but that was only a fantasy. He wasn’t quite used to the fact that Karen and he were finished—had to be finished. He wanted to see her, and he was sure she wanted to see him. But an evening together could only prove what they’d already proved half a dozen times in the past two months: what they had wasn’t a relationship, it was a crisis. He enjoyed her company and was genuinely fond of her, but she was painfully in love with him, wanted to be his wife. For different reasons, each of them wanted to be with the other, but both knew it had to be left alone to die.

Doing what people at loose ends do, Greg made a plan for filling up his evening. Then he carried it out.

The moment he opened his eyes in the garishly lit room above the liquor store, he knew where he was, and was annoyed with himself. To have stranded himself once again in his lawyer’s office was sheer stupidity and carelessness. It seemed so unnecessary, when he obviously wanted to be home in his own bed. With a sigh, he disentangled himself from the sheets, stood up, and straightened his clothes. Then, without having to think about it, he knelt beside the bed and groped among the dust bunnies for the key. He thought, If I’m going to keep on falling asleep here, I’ve got to clean up this mess.

The Story of B

The Story of B A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife: On the Other Side Known Commonly as the Little Book

A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife: On the Other Side Known Commonly as the Little Book Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit

Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit CLONES: The Anthology

CLONES: The Anthology Tales of Adam

Tales of Adam The Holy

The Holy Dreamer

Dreamer Beyond Civilization: Humanity's Next Great Adventure

Beyond Civilization: Humanity's Next Great Adventure After Dachau

After Dachau If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways.

If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways. Providence

Providence My Ishmael

My Ishmael Beyond Civilization

Beyond Civilization If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways

If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways Ishmael

Ishmael Ishmael i-1

Ishmael i-1 A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife

A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife