- Home

- Daniel Quinn

Beyond Civilization: Humanity's Next Great Adventure Page 11

Beyond Civilization: Humanity's Next Great Adventure Read online

Page 11

But can't an X be a tribe?

This is a question I'm asked again and again—substituting various terms for X. For example, I've been asked if an alreadyestablished conventional business can be converted into a tribal one. Yes, possibly, but with difficulty, the main one being that most people involved in conventional businesses are there for a wage, period. Some, having climbed up the wage scale, wouldn't care to climb down. Just as these might not be happy having less than a wage, others might not be happy having more than a wage—they just want to do their work and go home. But of course nothing's impossible.

A student in my Houston seminar asked if a bunch of people couldn't just get together and live tribally, and make their living elsewhere, individually. Certainly, and this is fine, but this is a commune, not a tribe, precisely because they're not involved in making a living together.

But can't a tribe be a commune—and can't a commune be a tribe?

We need some background to get at these questions.

Communities and tribes: origins

Like Topsy, most of the communities we inhabit just “grow'd,” without mother or father, as it were. Once upon a time a century ago—or two or five—a general store was joined by a feed store, a butcher, a livery stable, a smithy, a tavern, and these were soon joined by a bank, a dry goods shop, a boarding house, a lawyer, a barber, a doctor, and so on. At some point or other, all realized they had a stake in the community's success—and in each other's success to a certain degree. The banker certainly wanted some grocer to succeed, but he didn't care whether it was Smith or Jones. The owner of the boarding house wanted some barber to succeed, but she didn't care whether it was Anderson or Adams.

Communes never begin in this haphazard way. They're “intentional” communities, originating among people who want to live together in pursuit of common ideals, usually in relative isolation. Communes are about living together and may or may not involve working together.

Tribes (and I speak here of “new” tribes, of course) originate among people who want to pool their energies and skills to make a living together. Tribes are about working together and may or may not involve living together.

Communities and tribes: membership

To the extent allowed by law and custom, ordinary communities make it their policy to exclude certain kinds of people and include all the rest. In other words, unless you belong to some abhorred race, religion, social class, or ethnic group, you're welcome to move in.

Communes proceed in the opposite way. Their policy is to include certain kinds of people and exclude all the rest. In other words, unless you subscribe to the group's special values (social, political, or religious), you're not welcome to move in. The tribal rule of thumb is: Can you extend the living to include yourself ? In other words, if you want to live out of the tribal occupation, you'll have to extend the group's earning power to the point where it covers you. This is exactly what Hap and C.J. did for the East Mountain News. We couldn't have included them in the business if they hadn't extended it by selling advertising.

Can't a tribe be a commune?

As I said above, tribes are about working together and may or may not involve living together. But tribal people can live together without becoming a commune. Speaking of artisan, trader, and entertainer minorities such as Gypsies, Norwegian Taters, Irish Travelers, and the Nandiwalla of India, anthropologist Sharon Bohn Gmelch notes specifically that the social organization of these groups is flexible and “at its core, noncommunal.”

The difficulty I see with a tribe becoming a commune is that communes traditionally choose their members on the basis of shared ideals. Shared ideals aren't irrelevant to tribal applicants, but they're overridden by the question “Can you extend our livelihood to include yourself?”

I can certainly say that it didn't occur to any of us on the East Mountain News that we should “start a commune.” The idea would have struck us as ludicrous.

The tribe isn't about living together but about making a living together.

Can't a commune be a tribe?

The answer is, “Yes, a commune can definitely be a tribe; it's just a problematical way to begin.”

Communes generally start with people who want to “get away from it all.” Separating themselves from a corrupt, materialistic, and unjust society, they typically want to live “close to nature” alongside people with similar ideals. Because they intend to live simply, making a living seems almost incidental. They may farm, produce craft goods, or commute to ordinary jobs. As time goes on, all may work out exactly as planned—or it may not. Rustic simplicity may be less charming than expected. Perhaps some become bored with the work. Nerves fray, ideals are forgotten, friendships dissolve, and the thing is soon over. Or it may take a different direction. The members may refocus their attention from ideals to making a living together in a way that's more satisfactory. Remember, however, that this group originally came together on an entirely different basis, so it will be luck rather than design if they actually have some occupational interests and skills in common.

It's rather like going shopping for groceries that start with the letter m—mustard, mango, mackerel, mayonnaise, macaroni, and so on—and then later wondering if you happen to have the ingredients for Cassoulet du Chef Toulousian. It could happen, of course, but it's not as likely as if you'd gone shopping for those ingredients in the first place.

“Let's do the show right here in the barn!”

In cinematic legend this catch phrase springs to Mickey Rooney's lips in half a dozen movies he made with Judy Garland in the 1940s. Whether it was ever uttered in any film, its meaning is clear. Everyone understands that it emanates from a troupe of young entertainers looking for a chance to show off their talents.

It's important to note that it doesn't emanate from a group of people trying to invent something they might do together. In fact, they're a group because they already know what they can do together. Show business brought them together in the same way that the newspaper business brought us together with Hap and C.J. We might have been the best of friends, but only the newspaper could have pulled us together into a tribe. If we'd made up our minds to open an antique store or a computer software business, Hap and C.J. would never have been involved, no matter how close to them we might have been.

I say all this in answer to a question that must be in the back of many minds: Can't a bunch of miscellaneous friends become a tribe? The answer is yes, just the way a commune can become a tribe. It's perfectly possible, it's just not very likely—unless that bunch of friends was drawn together in the first place by a common occupational focus (as were the Neo-Futurists).

Aren't the Amish a farming tribe?

The Amish are a religious sect, an offshoot of the Mennonites. Here's what makes them communal rather than tribal: If you apply for membership, they'll be much more interested in your religious beliefs and your moral character than in your agricultural ambitions.

A commune “can be” a tribe, just as a lighthouse “can be” a grain silo and a prom gown “can be” a nurse's uniform. But the fact remains that we give things different names because we perceive them as different things. In Colonial New England, the settlers started communes, not tribes, and they knew the difference. Tribes were for savages and communes were for civilized people.

People will also ask, “Isn't Ben & Jerry's a tribal business?” And the answer is, Ben & Jerry's was a tribal business when Ben and Jerry were the company's only employees, personally making ice cream in a four-and-a-half-gallon freezer and scooping it up for customers in a remodeled gas station in Burlington, Vermont. After that point, their business grew not by adding members to their tribe but by adding employees in the conventional way. Ben & Jerry's isn't a tribal business, it's a values-led business (which doesn't make it any less admirable). Can a values-led business be a tribal business? Of course. It just isn't automatically a tribal business.

It's not my intention (or within my power) to divest the word tri

be of its ordinary meanings. Rather it's my intention to invest it with a special one when used in the context of the New Tribal Revolution.

Noble savages?

While considering what it would take to start a health-care tribe, a physician mentioned the fact that medical professionals in our society generally have a pretty high standard of living— clearly implying that she perceived this to be some sort of obstacle or problem. A few questions revealed that she was unconsciously picturing the members of her health-care tribe as noble savages—too noble to charge for their services (and therefore unable to maintain the standard of living they're used to).

It's hard to know how to cope with this familiar bipolarity, which sees people as incapable of being anything but either totally selfish or totally altruistic. Like an on/off switch, they can only flop from one pole to the other. Tribal life functions in between these poles, and a tribe of totally altruistic individuals will fail as surely as a tribe of totally selfish individuals.

If a physician decided s/he would rather have a general practice in a small town than a specialized practice in a big city, would s/he expect to work for nothing? Of course not. People in small towns expect to pay for medical services. If a physician decides s/he would rather belong to a health-care tribe than to a conventional hospital, why would s/he expect to work for nothing? People know that physicians, whether they work in tribes or in hospitals, have to make a living just like everyone else.

An intermittent tribal business

As the 1973 film The Sting opens, we follow a pair of grifters, Johnny Hooker (Robert Redford) and Luther Coleman (Robert Earl Jones), as they work a short con known as the Jamaican Handkerchief on a man who, unbeknownst to them, is carrying money to mob boss Doyle Lonnegan (Robert Shaw). When Lonnegan learns of the con, he has Coleman murdered. To avenge his partner, Hooker decides to take Lonnegan for a really big score. As he sets this in train, we see that he belongs to a whole tribe of grifters, who generally make their living in straight jobs (for example as clerks or bank tellers) but who are always ready to come together as a tribe in one of the classic “big cons.” A striking point is made of their readiness. When the single, wordless signal is given, they instantly abandon their jobs. Without asking how big the score will be or what their share is, they come together smoothly to assemble an elaborate theatrical production called a “big store.” As in the circus, each member is supremely important when his or her moment comes. One studies Lonnegan to discover how to lure him into the con. Others work on sets, on costumes, on props. Though Henry Gondorff (Paul Newman) is clearly the boss, this doesn't make him uniquely important. All the jobs must be done—and the boss's is just one of them. In hierarchal organizations, the boss is a supreme being. In tribal organizations, the boss is just another worker. (This is exactly the way it was on the East Mountain News.)

My next tribal enterprise

Long before I identified the concept as tribal, I wanted to open a circus of learning such as I described in Providence and My Ishmael. Now I have a better idea of how to make this work in reality. Houston appeals to me because it isn't zoned, making it a crazy quilt of residential and commercial districts, and no one fusses if you run a business from your home. This makes it an ideal site for a learning circus, which combines spaces for working, exhibition, and performance to provide a center for work, play, performance, and education, involving (as teachers, performers, and participants) acrobats, jugglers, clowns, dancers, musicians, actors, set designers, magicians, lighting technicians, film makers, writers, potters, painters, sculptors, photographers, weavers, costumers, carpenters, electricians, and so on. No grades, no required courses, no tests—just learn all you want, whenever you want. Although open to all-age learners, it would make a marvelous resource for parents homeschooling their children, an option becoming more and more popular everywhere, with good reason. (Please note, however, that this isn't a “community learning center” for “studentdirected learning.” These are fine things, but I'm aiming at entertainment, not civic good works.) Someone asked why students would prefer this learning circus over a university. The two aren't competitive, and the strictly career-minded will surely prefer the more conventional of the two.

No timetable exists for this grand enterprise.

To distinguish is to know

It's important for me to point out (before others do) that I didn't invent tribal businesses; I just distinguished them from conventional ones and so made them especially visible. Now that you know what they are, you'll probably see them everywhere. In discussion with my seminar, Rennie brought to mind one we know in Portland, Oregon, the Rimskykorsakoffeehouse. This quirky local landmark, the creation of quirky local celebrity Goody Cable, almost has to be experienced to be believed. To take a table is to enter a special world that can really only be adequately described as tribal. When things get especially busy, customers will often be pressed into service to wait tables, and I know of one local author who waits tables one night a week just for the privilege of belonging to the tribe. There are often long lines of people waiting to get in; they like being there because the people working there obviously like being there.

Tribal people get more out of life.

Just think. It's taken me thirty thousand words to make those seven sound plausible.

The civilized hate and fear tribal people

People in traveling shows of every kind are viewed as exciting but dangerous people, people to be shunned when they're offstage. This is part of their allure, especially for the young. In past ages Gypsies were constantly suspected of stealing children, probably because more than a few children in fact succumbed to the lure of Gypsy life. It's long been suspected that the tribalism of the Jews has contributed to their demonization. And certainly no effort has been spared on our part to destroy the tribalism of native peoples wherever we find them. Their tribalism is the very emblem of their “backwardness” and “savagery.”

The civilized want people to be dependent on the prevalent hierarchy, not on each other. There's something inherently evil about people making themselves self-sufficient in small groups. This is why the homeless must be rousted wherever they collect. This is why the Branch Davidian community at Waco had to be destroyed; they'd never been charged with any crime, much less convicted—but they had to be doing something very, very nasty in there. The civilized want people to make their living individually, and they want them to live separately, behind locked doors—one family to a house, each house fully stocked with refrigerators, television sets, washing machines, and so on. That's the way decent folks live. Decent folks don't live in tribes, they live in communities.

Yet, oddly enough, as soon as you hold up the tribe as something desirable, decent folks will start insisting they're as tribal as any Bushman or Blackfoot.

Tribes and communities

Pressed into a hierarchal mold, the tribe becomes what the civilized call a community. Within the hierarchy of civilization in any age, community exhibits self-similarity at many different scales. The medieval Yorkshire village of Wharram Percy was a microcosm of feudal England, just as Evanston is a microcosm of modern America. This sort of fractal self-similarity between microcosm and macrocosm is, as John Briggs and David F. Peat point out, “a product of all the complex internal feedback relationships going on in a dynamical system” like our own. It's inevitable that Evanston—and East L.A. and Harlem and Broken Arrow, Oklahoma—are all going to reflect the hierarchal organization of our society as a whole, with rich folks here, middle-class folks here, and poor folks there. It doesn't matter that the rich of Evanston are better off than the rich of East L.A. or that the poor of Harlem are worse off than the poor of Broken Arrow. The structure is there.

The word community is itself an acknowledgment of decency and is withheld from the undeserving. Homosexuals struggled long and hard to become “the gay community,” but pederasts and pornographers don't stand a chance. Hoodlums, criminals, convicts, and religious fanatics don't have c

ommunities, they have gangs, mobs, populations, and cults.

I can imagine totally decent people being attracted to Objectivism or Voluntary Simplicity or Creative Individualism. I have a harder time imagining them being attracted to the tribal life. Maybe it's just me.

A parable about sustainability

An inventor brought his plans for a new device to an engineer, who looked at them and said, “What you've got here is systemically flawed, which means it'll destroy itself after just a few minutes of operation.”

“Not if it's well made,” the inventor replied. “Every part must be made of the finest material and to very exact specifications.”

The engineer had the device built, but it destroyed itself after just four minutes of operation. The inventor wasn't discouraged. “You didn't do what I told you,” he said. “You've got to use much finer materials—the finest available—and make the parts to the most exact specifications.”

The engineer tried again, and the new model worked for eight minutes. “You see?” said the inventor. “We're making tremendous progress. Try again, using even finer materials and more exact specifications.” The new device lasted for ten minutes. The engineer was told to build yet another model, using still finer materials and still more exact specifications. The new model lasted for eleven minutes.

The Story of B

The Story of B A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife: On the Other Side Known Commonly as the Little Book

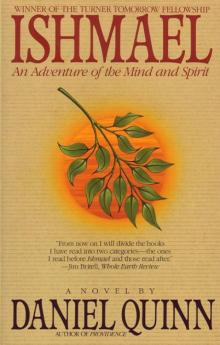

A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife: On the Other Side Known Commonly as the Little Book Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit

Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit CLONES: The Anthology

CLONES: The Anthology Tales of Adam

Tales of Adam The Holy

The Holy Dreamer

Dreamer Beyond Civilization: Humanity's Next Great Adventure

Beyond Civilization: Humanity's Next Great Adventure After Dachau

After Dachau If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways.

If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways. Providence

Providence My Ishmael

My Ishmael Beyond Civilization

Beyond Civilization If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways

If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways Ishmael

Ishmael Ishmael i-1

Ishmael i-1 A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife

A Newcomer's Guide to the Afterlife